- In-Stock Tumor Cell Lines

- Human Orbital Fibroblasts

- Human Microglia

- Human Pulmonary Alveolar Epithelial Cells

- Human Colonic Fibroblasts

- Human Type II Alveolar Epithelial Cells

- Human Valvular Interstitial Cells

- Human Thyroid Epithelial Cells

- C57BL/6 Mouse Dermal Fibroblasts

- Human Alveolar Macrophages

- Human Dermal Fibroblasts, Adult

- Human Lung Fibroblasts, Adult

- Human Retinal Muller Cells

- Human Articular Chondrocytes

- Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells

- Human Pancreatic Islets of Langerhans Cells

- Human Kidney Podocyte Cells

- Human Renal Proximal Tubule Cells

Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: An Autoimmune Disease Beyond the Thyroid

Graves’ ophthalmopathy (GO), also known as thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (TAO) or thyroid eye disease (TED), is a complex autoimmune disorder. It occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the muscles and tissues around the eyes, often in people who have Graves’ disease, a condition involving an overactive thyroid gland (hyperthyroidism).

GO is the most common extrathyroidal manifestation of Graves’ disease and can significantly impact patients’ quality of life. The condition is primarily characterized by progressive inflammation and expansion of the extraocular muscles, orbital fat and connective tissue, leading to a variety of signs and symptoms including eyelid retraction, periorbital edema, proptosis, diplopia and erythema of the periorbital tissues and conjunctivae, in severe cases, keratitis and optic neuropathy due to optic nerve compression [1].

For decades, the central cellular mediators of this debilitating disease remained incompletely characterized, however, emerging evidence has unequivocally established a specific cell population as central to its pathogenesis: the human orbital fibroblast.

Orbital Fibroblasts: Beyond Structural Support

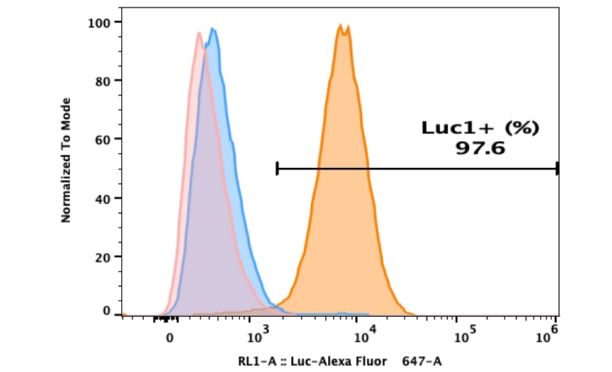

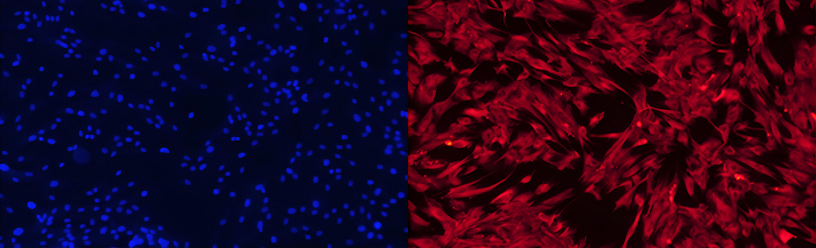

Orbital fibroblasts (OFs), traditionally defined as structural cells, are primarily responsible for synthesizing and organizing the extracellular matrix (ECM), thereby providing critical mechanical support and architectural integrity to orbital tissues. As illustrated in Figure 1, primary human OFs exhibit characteristic morphological and immunocytochemical features. Staining with DAPI and vimentin confirms the mesenchymal origin and high purity of the isolated cell population, underscoring the efficacy of the isolation and purification protocols employed by AcceGen.

Figure 1. Primary human OFs stained with DAPI and vimentin.

Within the pathological context of GO, OFs exhibit a more dynamic role, they transition from a quiescent state to active participants in disease progression. Importantly, OFs represent a heterogeneous population, with phenotypic and functional distinctions between fibroblasts derived from orbital adipose and connective tissues (Thy-1⁺) and those originating from the extraocular muscles (Thy-1⁻). These subpopulations demonstrate divergent differentiation potentials, influencing their contributions to disease pathology [2].

Critically, in GO, OFs serve both as primary targets of the autoimmune attack and as principal effector of tissue remodeling. They express key autoantigens recognized by the immune system, most notably the thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) and the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R). This dual functionality positions OFs as central regulators through which autoimmune signaling is transduced into the clinical manifestations of GO.

Dual Pathogenic Mechanisms: Inflammation and Tissue Remodeling

The pathogenesis of GO mediated by OFs involves two interrelated processes: a sustained inflammatory cascade and a dramatic process of extensive tissue remodeling. These mechanisms operate in a synergistic and self-amplifying manner, perpetuating disease progression.

Immune Activation and Inflammatory Cascade

Disease initiation involves OF activation via autoantibodies, particularly TSHR-stimulating antibodies (TSAbs) produced by B-cells, and pro-inflammatory cytokines released by infiltrating immune cells such as T-lymphocytes and macrophages. Key cytokines, including interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and CD40 ligand (CD40L), directly stimulate OFs [3].

Upon activation, OFs become prolific sources of inflammatory mediators. They secrete chemokines such as CCL2, CCL5, CXCL9, CXCL10, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-16 which function as potent chemoattractants, recruiting additional T-lymphocytes, B-lymphocytes, monocytes and neutrophils into the orbital space. This recruitment further amplifies the local inflammatory milieu [4]. Additionally, activated OFs produce substantial quantities of prostaglandin E₂ (PGE₂), a key contributor to vasodilation, edema, and pain during the active inflammatory phase of GO. This autoregulatory inflammatory circuit represents a defining feature of the disease.

Differentiation and Fibrosis: Structural Alterations in the Orbit

The functional and phenotypic heterogeneity of OFs is fundamentally linked to their distinct differentiation potentials, which are principally determined by two major subpopulations: Thy-1⁻ and Thy-1⁺ OFs. Thy-1⁻ OFs, primarily derived from the orbital adipose compartment, possess a pronounced capacity for adipogenesis. In contrast, Thy-1⁺ OFs, predominantly originating from connective tissues and the perimysium of extraocular muscles, exhibit a limited adipogenic potential but a high propensity to differentiate into myofibroblasts, particularly when stimulated by profibrotic cytokines such as the Th2-associated transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). Myofibroblasts, characterized by α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression and enhanced contractile activity, are the principal effector cells responsible for excessive collagen deposition and tissue contraction, thereby driving the fibrotic remodeling observed in GO [1, 5].

Following immune activation, OFs undergo a phenotypic shift marked by increased proliferative activity and sustained secretion of inflammatory mediators. Concurrently, their differentiation into adipocytes and myofibroblasts initiates a pathological cycle of tissue expansion and fibrosis. A critical outcome of this activated state is the dysregulated overproduction of ECM components. Both immune-derived signals such as IL-1, TNF-α, TGF-β, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and direct cellular interactions with infiltrating lymphocytes and macrophages potently stimulate OFs to synthesize hyaluronan (HA), a glycosaminoglycan that accumulates pathologically within the orbital space. Due to its marked hydrophilicity, HA binds water molecules a thousand times to its weight, leading to profound edema and increased tissue volume within the rigid confines of the bony orbit [6]. This HA-mediated tissue expansion underlies many of the salient clinical features of GO.

An Integrated Pathogenic Model

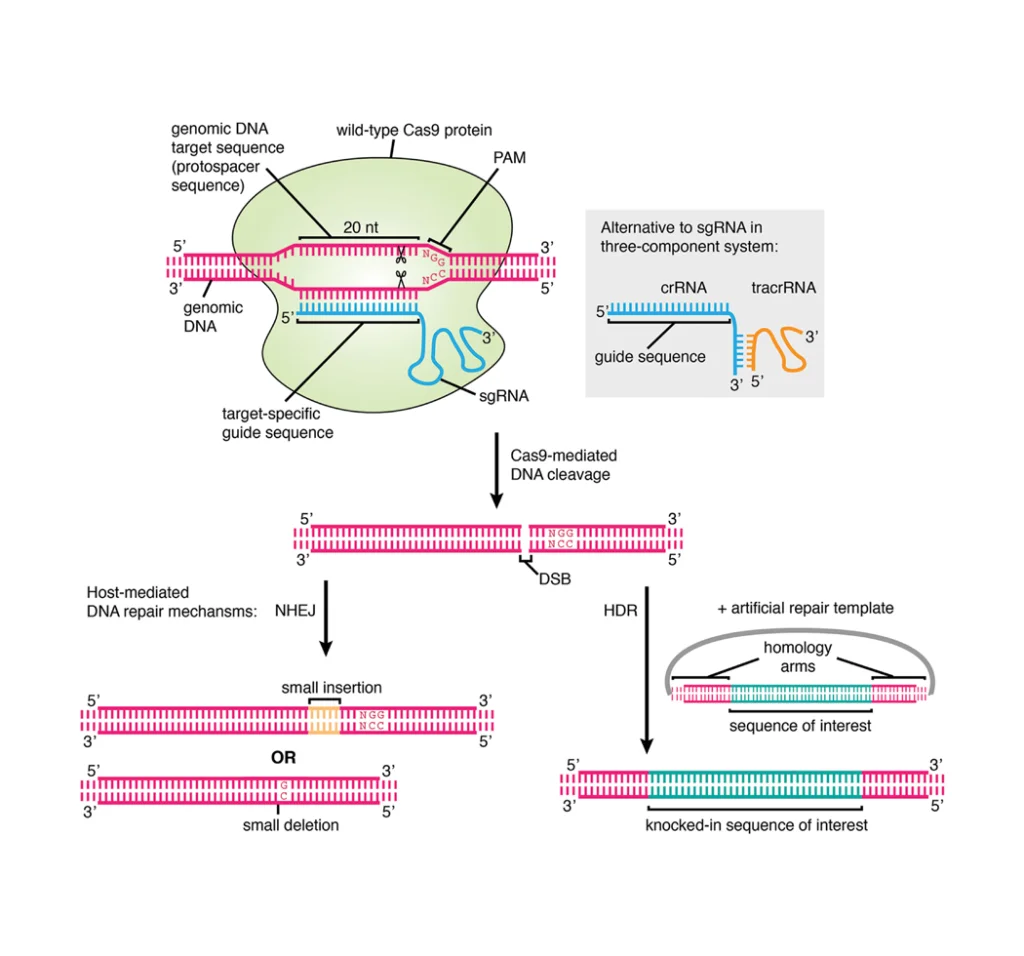

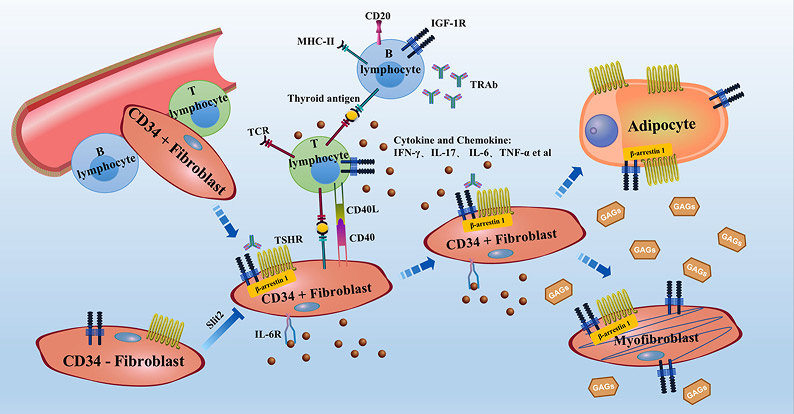

The central role of OFs in integrating immune signals into the structural pathology of GO is summarized in Figure 2. The proposed model begins with the migration of circulating fibrocytes into the orbit, which express thyroid-related antigens such as TSHR. B lymphocytes, macrophages and activated T lymphocytes within the orbital microenvironment then engage and activate resident OFs through cytokine release and direct cell-to-cell contact. Activated OFs perpetuate a localized inflammatory response via cytokine and chemokine secretion, which recruits additional immune cells. Simultaneously, they overproduce glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), predominantly HA, leading to tissue edema and expansion. The subsequent differentiation of OFs into adipocytes (contributing to adipose tissue expansion) and myofibroblasts (driving fibrosis and muscle thickening) culminates in the hallmark structural changes of GO: orbital edema, increased orbital fat volume, extraocular muscle enlargement, and exophthalmos [7].

Figure 2. The central role of OFs in the pathogenesis of GO.

Conclusion and Future Perspective: Targeting Orbital Fibroblasts for Precision Therapy

Accumulating evidence from 2020 to 2025 solidifies the role of human OFs as the central orchestrators of pathology in GO. Their dual function as both target and effector in the autoimmune response renders them a compelling focus for novel therapeutic strategies. Current research is shifting from generalized immunosuppression toward precision interventions that directly modulate OF behavior.

Recent clinical and translational studies have identified several promising therapeutic avenues. A 2025 investigation demonstrated that nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, effectively suppresses both fibrotic and adipogenic differentiation in GO-derived OFs in vitro [8], suggesting a potential strategy to curtail tissue remodeling. Another innovative approach involves a TSHR-targeting nucleic acid aptamer that acts as an allosteric inhibitor, exhibiting high orbital tissue specificity and effectively blunting autoimmune activation at the fibroblast level [9].

Additionally, signaling pathways mediated by PDGF-BB and TGF-β remain high-priority targets. Preclinical studies indicate that dasatinib, a small molecule inhibitor of PDGF-induced fibroblast activation, holds therapeutic promise [10], while strategies to modulate TGF-β—a key driver of fibrosis—are under active investigation [11]. The growing focus on OF-directed therapies was highlighted at the 2025 EUGOGO International Symposium, which emphasized novel pharmacologic agents and ongoing clinical trials aimed at core GO mechanisms. These advances signify a paradigm shift in GO management—from symptomatic control toward disease modification through precise targeting of OFs. The future of GO therapy lies in these targeted modalities, offering the prospect of more effective and better-tolerated treatments for affected patients.

| Cat. No | Product Name | Cell Type | Price |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABC-TC077G | Human Orbital Fibroblasts | Primary Cells | +inquiry |

| ABI-TC002W | Immortalized Human Orbital Fibroblasts | Immortalized Cell Line | +inquiry |

References

[1] W.A. Dik, S. Virakul, L. van Steensel, Current perspectives on the role of orbital fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of Graves’ ophthalmopathy, Experimental eye research 142 (2016) 83-91.

[2] T.K. Khoo, M.J. Coenen, A.R. Schiefer, S. Kumar, R.S. Bahn, Evidence for enhanced Thy-1 (CD90) expression in orbital fibroblasts of patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy, Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association 18(12) (2008) 1291-6.

[3] T.J. Smith, L. Hegedüs, Graves’ Disease, The New England journal of medicine 375(16) (2016) 1552-1565.

[4] D. Łacheta, P. Miśkiewicz, A. Głuszko, G. Nowicka, M. Struga, I. Kantor, K.B. Poślednik, S. Mirza, M.J. Szczepański, Immunological Aspects of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy, BioMed research international 2019 (2019) 7453260.

[5] D.Y. Shu, F.J. Lovicu, Myofibroblast transdifferentiation: The dark force in ocular wound healing and fibrosis, Progress in retinal and eye research 60 (2017) 44-65.

[6] T.J. Smith, Participation of Orbital Fibroblasts in the Inflammation of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy, in: R.S. Bahn (Ed.), Thyroid Eye Disease, Springer US, Boston, MA, 2001, pp. 83-98.

[7] X. Cui, F. Wang, C. Liu, A review of TSHR- and IGF-1R-related pathogenesis and treatment of Graves’ orbitopathy, Frontiers in immunology 14 (2023) 1062045.

[8] H.Y. Park, S.H. Choi, J. Ko, J.S. Yoon, Therapeutic effect of nintedanib in orbital fibroblasts in patients with Graves’ orbitopathy, Immunopharmacology and immunotoxicology 47(3) (2025) 406-418.

[9] Y. Zhang, E. Wu, W. Liu, L. Zeng, N. Ling, H. Wang, Z. Li, S. Yao, T. Pan, X. Li, Y. Huang, X. Li, Y. Tu, W. Yan, J. Wu, M. Ye, W. Wu, TSHR-Targeting Nucleic Acid Aptamer Treats Graves’ Ophthalmopathy via Novel Allosteric Inhibition, Advanced science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany) (2025) e05586.

[10] S. Virakul, L. van Steensel, V.A. Dalm, D. Paridaens, P.M. van Hagen, W.A. Dik, Platelet-derived growth factor: a key factor in the pathogenesis of graves’ ophthalmopathy and potential target for treatment, European thyroid journal 3(4) (2014) 217-26.

[11] H.H. Chang, S.B. Wu, C.C. Tsai, A Review of Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Strategies Targeting TGF-β in Graves’ Ophthalmopathy, Cells 13(17) (2024).

Copyright - Unless otherwise stated all contents of this website are AcceGen™ All Rights Reserved – Full details of the use of materials on this site please refer to AcceGen Editorial Policy – Guest Posts are welcome, by submitting a guest post to AcceGen you are agree to the AcceGen Guest Post Agreement – Any concerns please contact marketing@accegen.com